Publications

Like Hopper, Dreyfack is perhaps more interested in the formal exploration of the ways in which light can be represented within [a] world of darkness.

–From the introduction by David A. Ross

It seems obvious once you think about it, how any even-slightly ambitious creation must spring from the artist’s depths. This so seemingly obvious realization came to me only toward the end of the formulation of this work. It happened during the opening days of a photography portfolio review session in late April 2019 in Portland, Oregon.

I had brought my portfolio to Portland with the specific goal of finding a publisher for the body of work which I had been building over the past five years. I had carefully prepared my prints and my pitch for the publishers I hoped to meet at the session. But surprisingly, I had not prepared a response to their query about a text to accompany the images. A fellow who had earned his living as a writer and journalist for the past 40 years failed to devote even a passing thought to text.

One publisher suggested the possibility of assigning a prominent photography critic to write a foreword. Another, noting the advantage of a widely-recognized name, asked whether I knew anyone more-or-less famous. I told them I would think about it – which I did over the course of a few sleepless nights.

This is the result of those sleepless nights:. not simply this text or the others scattered through this volume, but much of the backbone underpinning this work. After my eureka moment, I understood that, for better or for worse, the thread holding all the images together could only be me and my own unique factory of facts.

Out went the images from London, Istanbul, Albuquerque. In came more images from Paris and its suburbs. In too came a series of short texts not to describe or explain the images but to inform them by suggesting why they are so often bathed in solitude, darkness or alienation.

For me, Silent Stages has grown into a deeper, more personal work – but not a sadder one – thanks to these changes. It has evolved into a visual memoir of sorts, composed not of images of the specific people or places of my life but rather of the sediment and juxtaposition that have accumulated and resonated across the years.

Ken Dreyfack

May 2019

Additional text no included in the book

King of New York

I was still in college when I began what was to become a 20-year journalism career. My first job was writing scripts for 22-minute newscasts at an all-news radio station in New York. I reported for work between 3 and 4 a.m. to prepare material for morning drive time. Later, working the overnight shift at the Associated Press, I again found myself in the heart of Manhattan during the hours when nightlife was mostly finished and the new day had yet to start. With the streets empty save for cleaning and maintenance workers and the occasional drunk, I sometimes felt drunk myself, high on the sense that I was among the privileged few who knew the city more intimately than the masses who crowded in at other times. In the quiet darkness, I could imagine I was the king of New York.

Sunday Morning

Two paintings I saw as a kid at the Met and Whitney museums in New York had a particular impact on me. I would be sure to spend time with them each time I visited. One was Pieter Brueghel’s The Harvesters. For some reason, I connect the other, Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning, with my paternal grandparents, who had both died before my fifth birthday. Might there have been some resemblance between the red brick structures in Hopper’s painting and the building where they lived, of which I have no conscious recollection?

Sidewalks

I had been living in Paris (again) since 1987 when the 9/11 terrorist attacks happened. I watched the events unfold live on CNN International from my office near the Gare Saint-Lazare. Once I knew that my oldest son, whose office was nearby, was safe, I thought I was at a comfortable distance from the horror. That’s why, during the ensuing days, I couldn’t understand why I felt so distressed, unable to sleep, breaking unexpectedly into tears. When I told a therapist that images of city sidewalks haunted my thoughts, he suggested they came from my childhood in the Bronx, where the sidewalks had been our playground. By attacking the place of my childhood, the terrorists were threatening a cornerstone of my identity.

The Invisible Wall

During my first year in college in New Jersey, I was taken under the wing of the grad student who was my freshman English teaching assistant. Among other common interests, we were both avid jazz fans. When I complained that I could not afford to regularly travel into New York to enjoy the city’s bustling jazz scene, he offered to help me get work as a copywriter at the all-news radio station where he freelanced. Thanks to him, I was soon working the 4-a.m.-to-noon shift Sunday mornings. Unintentionally, almost unconsciously, I became a journalist. I loved the excitement, the relentless pace, and the privileged access to people and information unavailable to others. As a journalist, you’re required to keep a distance from your subject. It became second nature to me, maintaining that invisible, impenetrable wall.

HomeMine

When I knew I’d be moving to Kingston, a small city 100 miles north of New York, I wanted to see whether I could mine it for the dramatic backdrops I needed for my ongoing Silent Stages project. Once I was actually living there, I discovered that photographing the city was a way for me to appropriate it. I began developing an affection for the place and a conviction that, in some uniquely personal way, it was becoming mine. This same sense of admittedly superficial possession arises regularly now, whenever I wander the dark, deserted streets and alleys of a town or city, camera in hand.

Silent Stages can be purchased for $45 plus $5 shipping (US domestic postage).

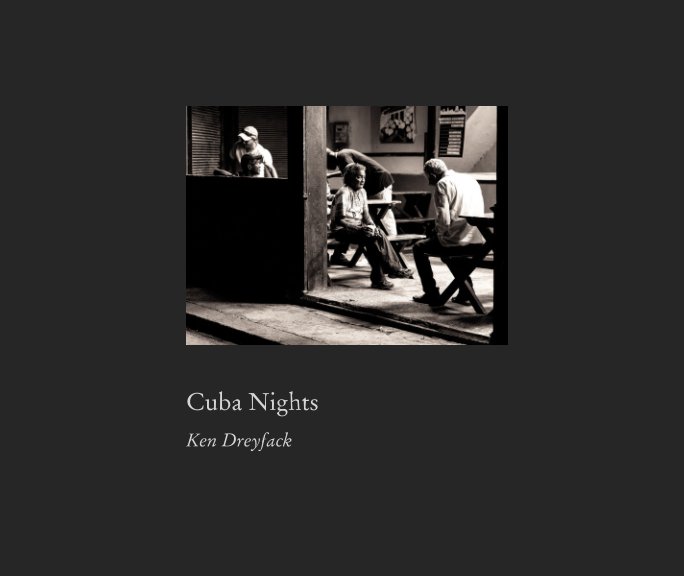

I had the privilege and pleasure of visiting Cuba, for the first time, in mid-February. For ten-days, camera in hand, I wandered the streets of Havana, Trinidad, Camagüez and Santiago, discovering their look and feel, eagerly gathering initial impressions of the country and its people. Now, just six weeks later, it feels as if I traveled during a bygone era.

At the time of my trip, the covid-19 virus was just another distant blip on the endless chain of events that make up the news of the day. Today, holed up in my home, fearful even to take the paper in from the front stoop without gloves and disinfectant, it has become unthinkable to stroll carelessly through the deserted streets of my own city, much less those of a foreign land.

Reviewing and sequencing these images now, six weeks later, they appear not only of another era but also premonitory. The isolation and alienation that inspire them seem appropriate to a disease-infested world where fear of contagion is pervasive and social distancing is a prerequisite to survival.

Ken Dreyfack

April 3, 2020